To celebrate Bicycle Day on April 19th, the date of Albert Hofmann’s—and the world’—first LSD trip in 1943, we are publishing this excerpt from the forthcoming interview with Michael Horowitz—the third installment of the Acid Bodhisattva series, coming soon to timothylearyarchives.org.

To celebrate Bicycle Day on April 19th, the date of Albert Hofmann’s—and the world’—first LSD trip in 1943, we are publishing this excerpt from the forthcoming interview with Michael Horowitz—the third installment of the Acid Bodhisattva series, coming soon to timothylearyarchives.org.

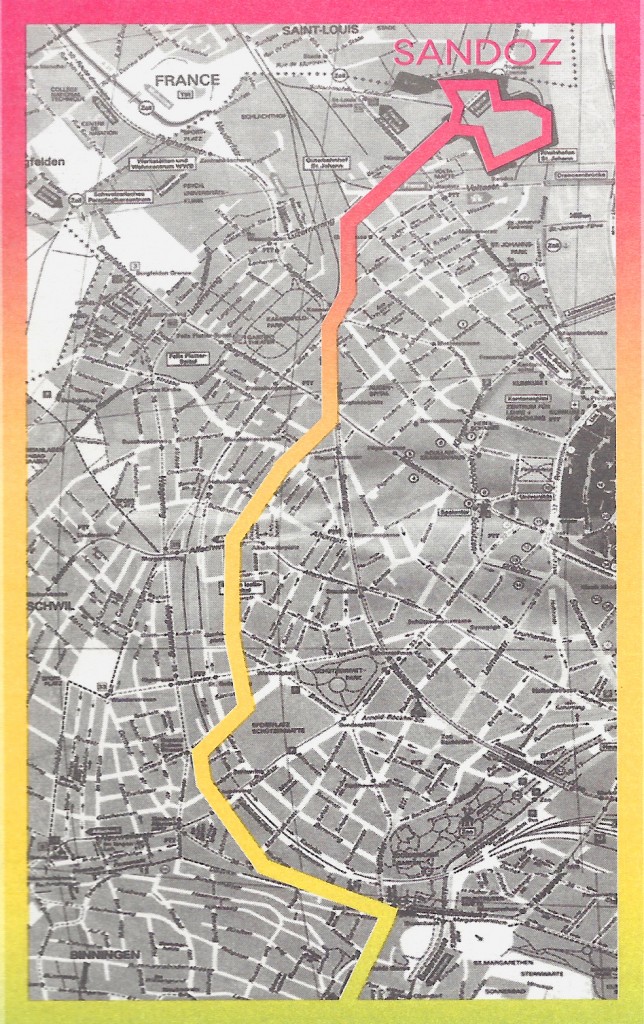

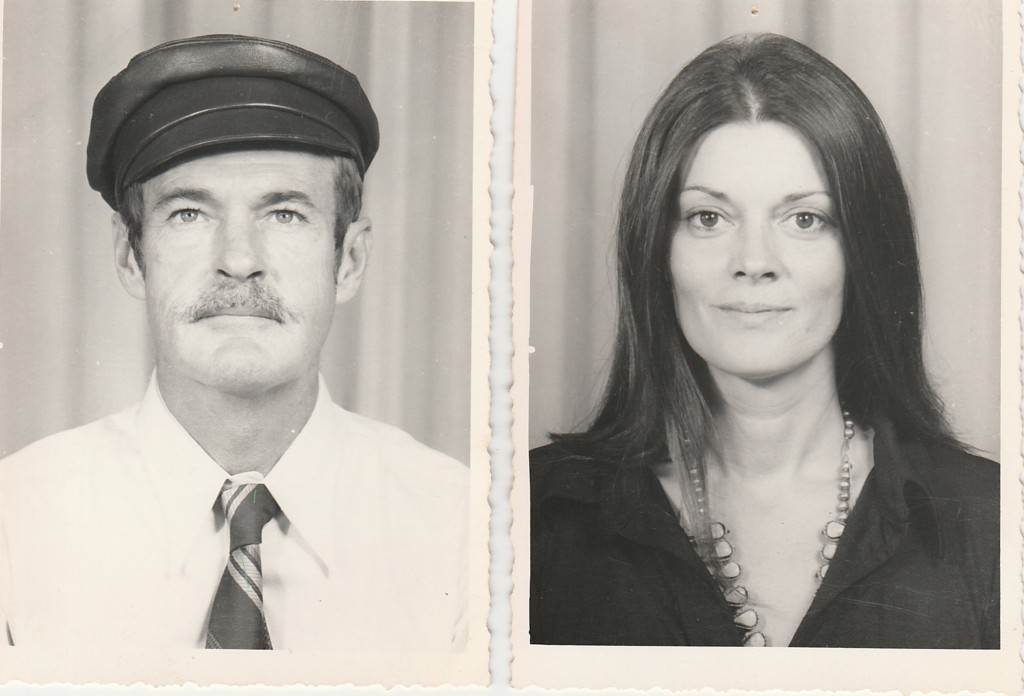

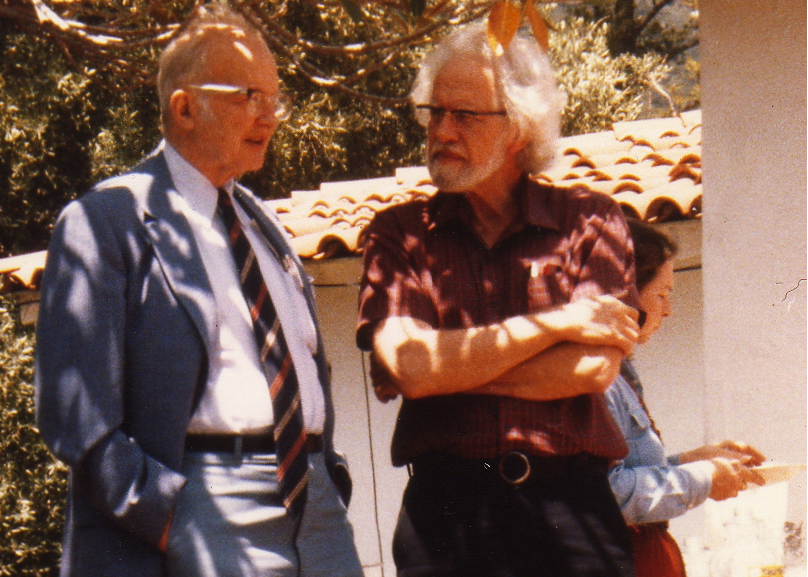

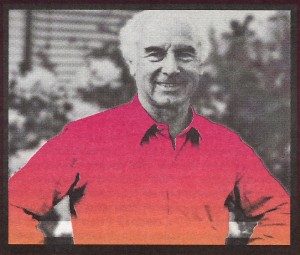

Images: from Lysergic World (April, 1993): Albert Hofmann in 1977 (left), and the route of his famous bicycle ride on LSD through Basel, Switzerland on April 19, 1943, from Sandoz Laboratories to his house (below).

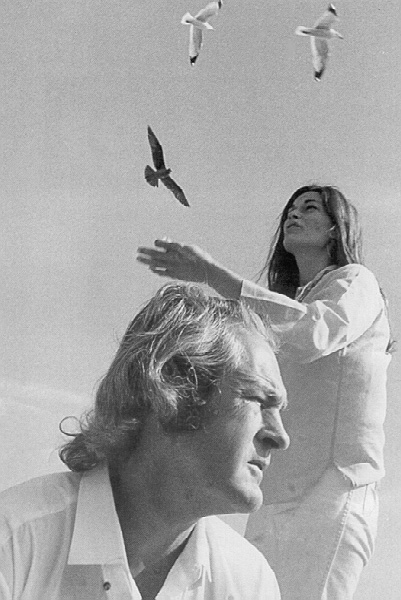

Leary’s archivist Michael Horowitz reminisces about a car ride with Albert Hofmann and Timothy Leary in February 1972.

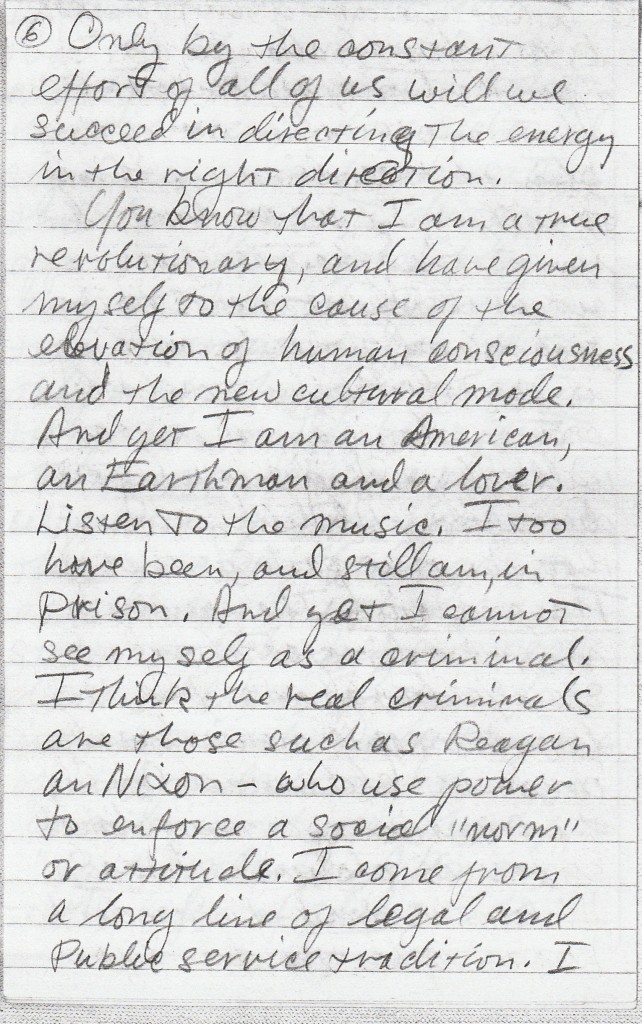

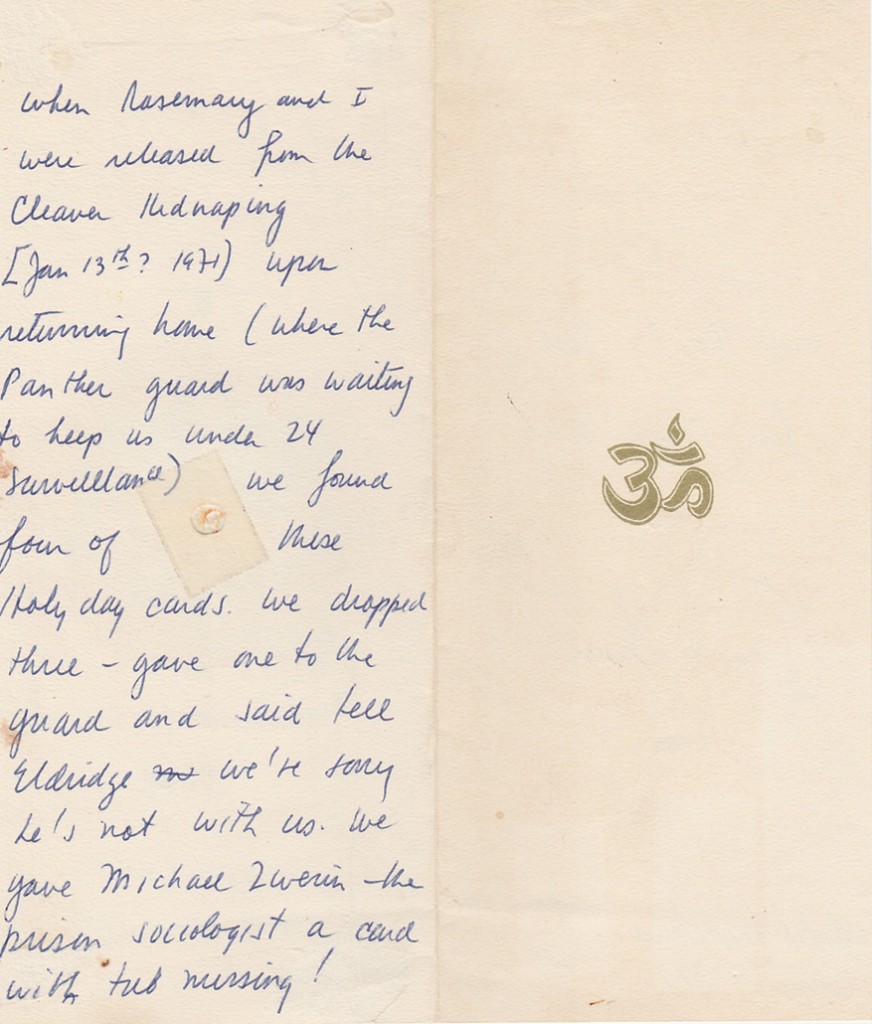

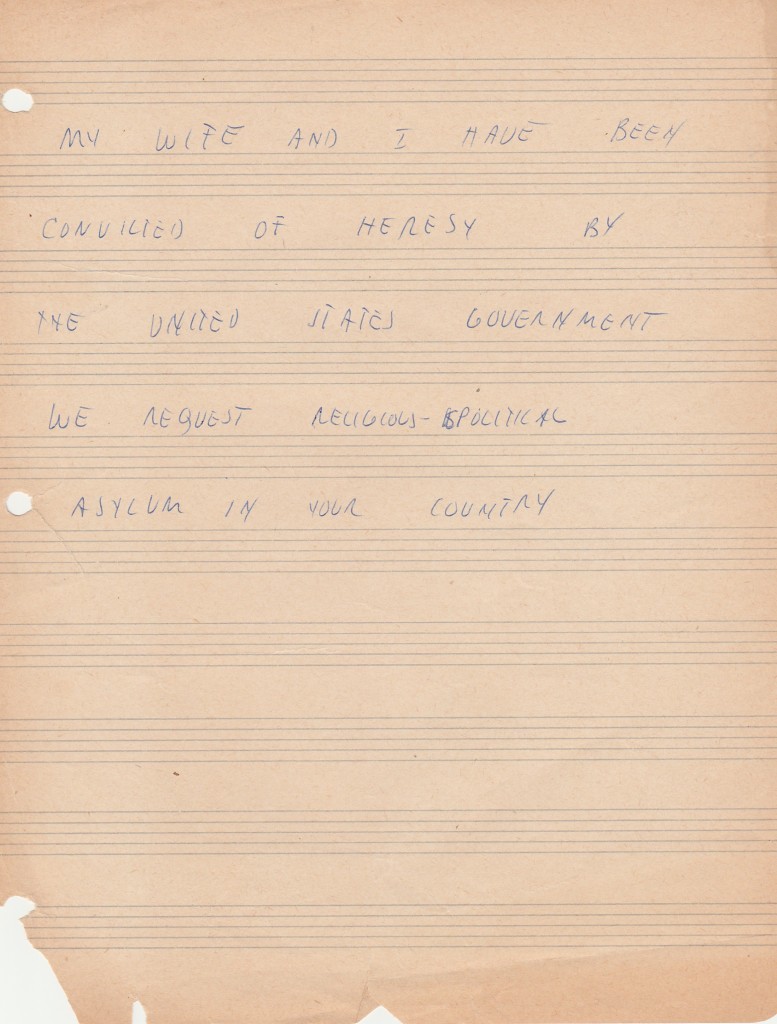

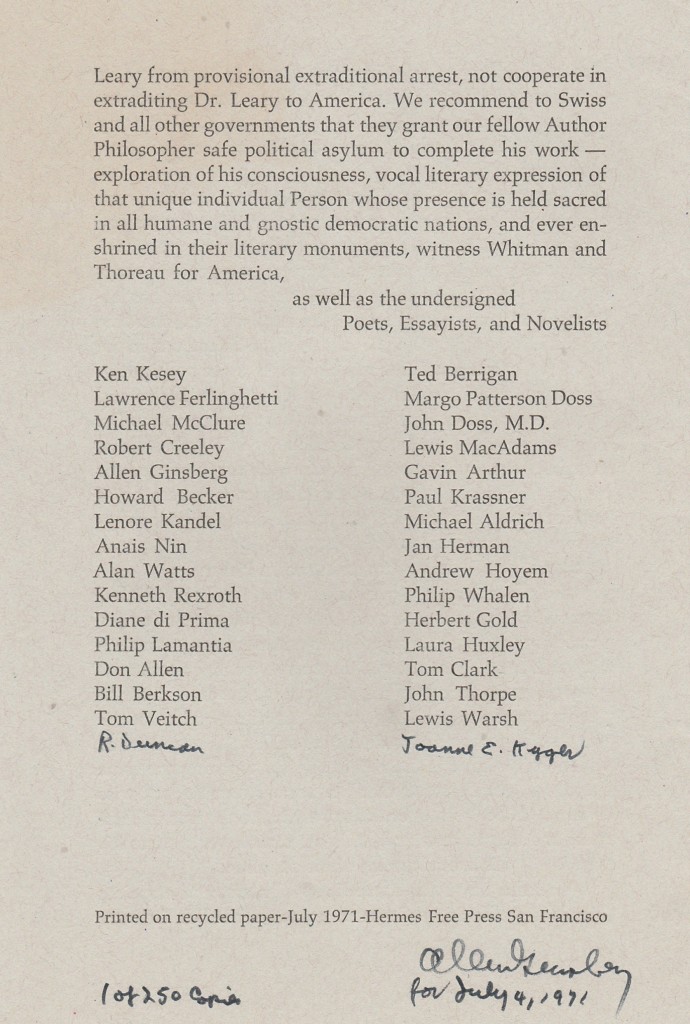

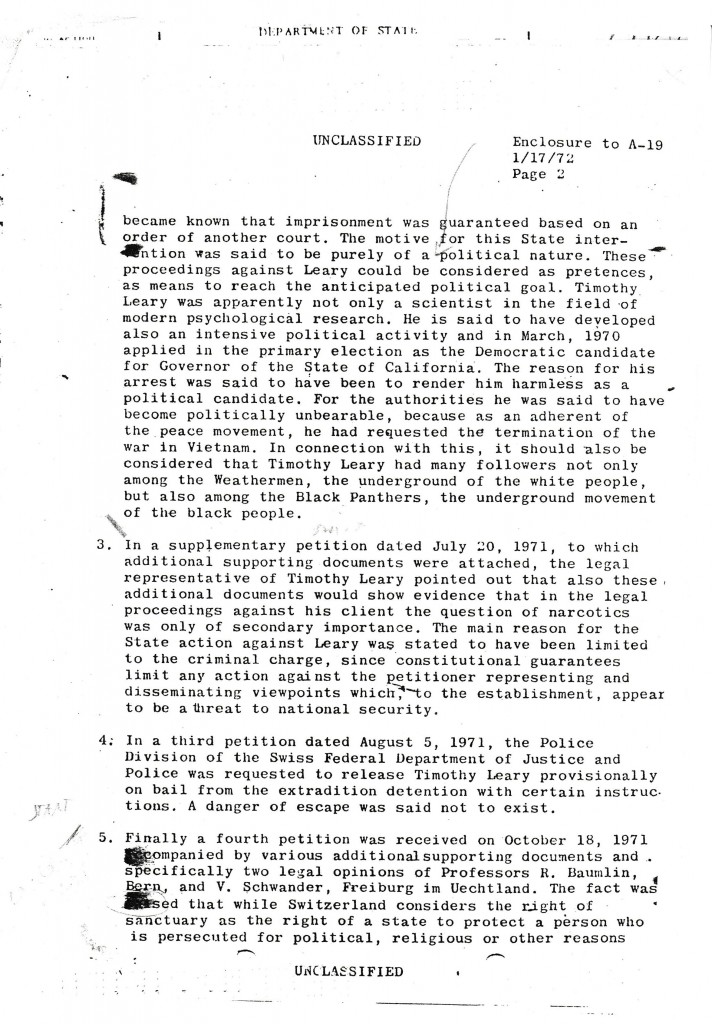

“Tim and I took the train to Basel where Albert picked us up in his car. He drove, Tim sat in the passenger seat and me in back, trying to manage a super 8mm movie camera with one hand and a tape recorder with the other. Albert told us that we were driving the route of his first LSD trip in 1943, when he bicycled home with his Sandoz lab assistant after testing 250 micrograms. Tim cracked up when I asked Albert if he still had the bicycle. I knew it was gauche of me, but I couldn’t resist. A short time later Albert pulled over.”

Here is an excerpt of the conversation between Albert and Tim, after they picked us up at the train station. On the way to Albert’s estate we passed by his 1943 home.

Albert: That house is where we lived at the time. I never thought I would get home that day. My assistant who had ridden with me at my request asked permission to leave. I told her fine, but in fact I was in a panic. My wife and children were away. It was just me. I barely managed to crawl to my bed.

Timothy: It was the first bad trip, too. There was no precedent. You must have thought you’d poisoned yourself.

Albert: But in the end it was good. In the morning it was fantastic.

Timothy: For me, the world changed forever. I would have remained a boring professional psychologist the rest of my life, making money and accomplishing nothing.

Michael: Instead of being the most dangerous man in the world.

Timothy: Right.