How a scholarly hippie got pulled into the orbit of the psychedelic revolutionary whom then-President Nixon labelled “the most dangerous man in America”

Lisa Rein conducts the first in-depth interview of Timothy Leary’s longtime archivist, Michael Horowitz

Part 2: November 1970 – August 1971

LR: So,Tim escapes from prison and he and Rosemary land in Algeria with the Black Panthers. I mean, wow. No one expected anything like that, right? Were you surprised?

MH: It pretty much stunned everyone, but it made sense. They had to leave the country, and Europe would not be safe. Algeria was home to a number of exiled liberation movements. The government had recently allowed Eldridge Cleaver, another American fugitive, to establish the International Section of the Black Panther Party there.

LR: Did the Weathermen set it up?

MH: They arranged everything—getaway cars, safe houses, false passports, plane tickets. Bernardine Dohrn herself shaved Tim’s head, turning him into William J. McNellis, a bald, bland American businessman. They took time out to drop acid and see the Woodstock movie in disguise. Leary added a psychedelic dimension to the militant wing, as he could articulate the re-imprinting value of LSD as an antidote to the government propaganda being churned out by the mainstream media, and link it to the history of heresy in Western Civilization.

LR: Looking back, it seems the counterculture comprised a number of very different movements finding common ground.

MH: Yes. There were philosophical and tactical divides within the many branches of the Movement, all deeply opposed to the Establishment. On the cusp of the ’70s Leary was intersecting with three of the most badass: the Brotherhood of Eternal Love (dope), Weatherman (bombs) and the Black Panther Party (guns).

LR: What was the scene like in Algiers?

MH: Algeria was the refuge for a host of international revolutionary groups. Cleaver, the Panther Minister of Information, had jumped bail and fled there via Cuba. Other members of the Panthers were setting up social programs in Oakland, when they weren’t in direct confrontation with the cops. Huey Newton had just been released from the same prison Leary escaped from.

Newsweek published a photo of Cleaver and Leary in Algiers captioned “Privileged Exiles,” dissing the American revolutionaries for being in “the favored haven for au courant fugitives and expatriates.”

“I fled to Algeria in 1970 under the madcap illusion that Cleaver and [Algerian president Houari] Boumedienne planned to sponsor a broad-based coalition-liberation movement of American political fugitives. This was the hysterical era when the Nixon-Mitchell clique had publicly announced its intention to imprison all political enemies” — Timothy Leary – From “Timothy Leary Drops a Line (from Somewhere in Federal Custody),” City of San Francisco, July 1975.

LR: How did it go between Tim and Eldridge?

MH: Cleaver felt they had a lot of common ground and the Learys could make a positive contribution to the Panther position as an international revolutionary force. It didn’t turn out that way.

LR: Why not?

MH: Because, although Tim and Rosemary were thrilled to be together and free, they couldn’t quite behave like the serious revolutionaries Cleaver expected them to be. While they adopted the guerilla rhetoric and spoke eloquently about it in the underground press, in real life, their behavior was too loose and broke many of the Panther’s protocols. They attracted hippie and yippie visitors with whom they hung out and turned on. Ignoring travel restrictions, they slipped away to Bou Saada for some psychedelic R & R.

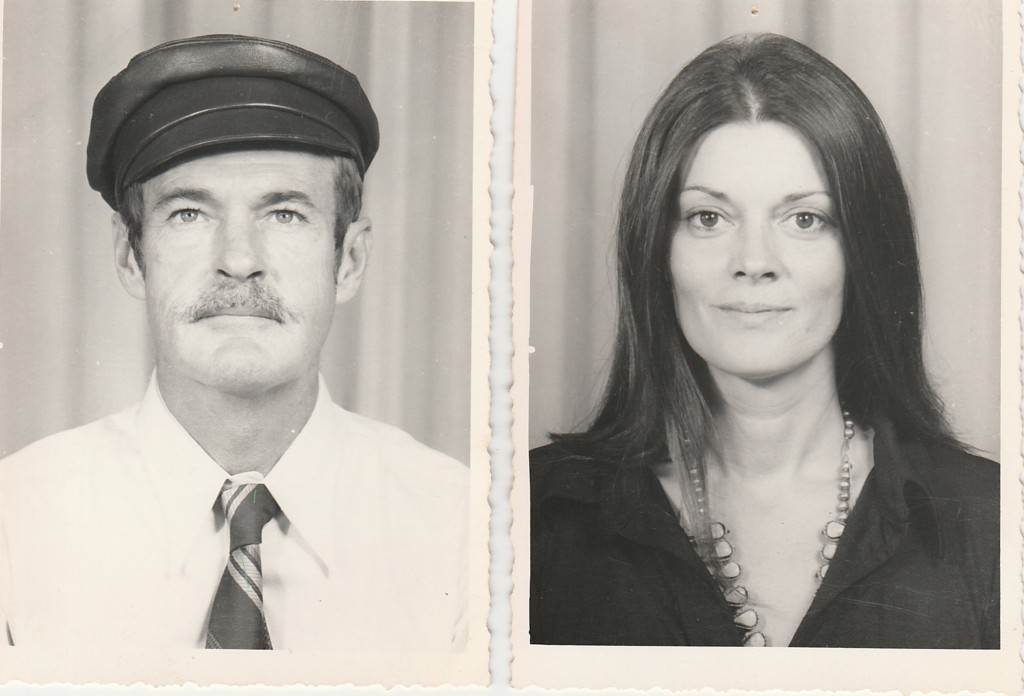

Tim and Rosemary Leary in Bou Saada, Dec. 1970. Rosemary captioned this photo, “At times, in deep space, tensions develop giving rise to bizarre emotions. The crew finds its outlet in unusual ways.” Photo: Louis Gimenez. Horowitz Archives

One visitor brought them a cassette player stashed with LSD. It freaked out Cleaver who worried about surveillance from the Algerian government, as well as informants, FBI, CIA—“the armies of Babylonian agents,” as he called them.

Eldridge ran a tight ship by necessity and the Learys couldn’t adapt to that. It was a clash between the hedonic and the political revolutions that was going to lead to a highly-publicized confrontation a few months later.

LR: What were you doing during this time?

MH: While Tim and Rosemary were settling in with the Panthers, Bob Barker and I took a road trip across the U.S. with the final draft of Leary’s prison book, Jail Notes, to bring to the publisher in New York City. We stopped in Chicago to meet with the editors at Playboy and offer some shorter pieces Tim had written in prison, but they declined to publish. Hefner had been welcoming in the ‘60s, but now there was a noticeable chill from people who didn’t know what to make of the new kickass Leary. They published an unflattering piece on him a few months later.

We stopped in Madison to visit STASH (Student Association for the Study of Hallucinogens), a group of turned on college student-scholars who were our counterparts in the Midwest.

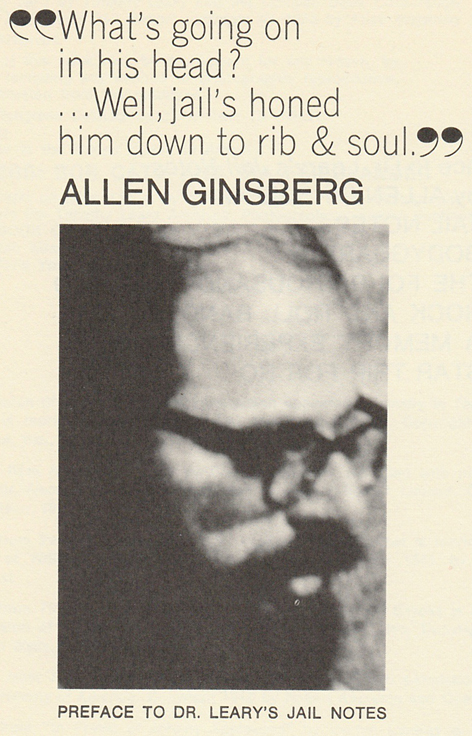

Next was a visit to Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky’s farm in Cherry Valley, New York, to meet them for the first time, at Tim’s urging. Ginsberg had written me after hearing about us from Tim. He was taken with the Bodhisattva name. We revered Allen, both as poet and activist, and it was empowering to have his support.

Dear Bo—

Kerouac used the Bo of Hobo for American Bodhisattva… Hey Bo!

Your plans sound excellent and I just pray you are a steady solid quiet cat who can safeguard & index & prepare mss. like a lovely scholar over years. When you have any specific word for me to put in anywhere please do call on me. I wrote a short 3-page addenda to Jail Notes mss. which together with earlier extensive essay on Tim in “Village Voice” can serve as a lengthy preface to the book, all dignified, like. Your letter if you follow up is really a bright ray. Allen G.”

MH: We ate psilocybin mushrooms that evening with partying Beat poets who were staying there. Before we left in the morning, Allen gave us the foreword to Jail Notes that he’d just finished typing. His position was: “What happens to Tim Leary will happen to America.”

LR: What exactly did he mean by that?

MH: That using drug laws to suppress dissent was the MO of the government, and that criminalizing free speech was going to lead to more and more injustice, especially aimed at the American youth culture.

When we said goodbye, he and Peter were in overalls standing in their garden. Allen was holding a pig they’d just acquired. He wished protestors would stop calling the police “pigs” because they got it wrong: pigs were loving animals, much nicer than cops.

LR: What was the dynamic between Ginsberg and Leary?

MH: The synergy between them was powerful. There’s a book devoted to their psychedelic partnership, White Hand Society. It went back to the Harvard period when Allen and Peter were subjects in the psilocybin experiments. Allen’s messianic enthusiasm for psychedelics was equal to Tim’s, and he brought him to New York City to turn on his Beat friends and jazz musicians. He introduced Tim—still a semi-straight academic–to the hipster culture. Tim had a sexual awakening on psilocybin with a beautiful model. Everyone loved the magic mushroom pills for their life-changing insights and shattering revelations, as well as their spiritual and sensual sides.

LR: Allen was a practicing Buddhist. What did he think of Tim’s alliances with the Weathermen and the Black Panthers?

MH: Their friendship was tested publicly when Ginsberg, like Ken Kesey and others, challenged the militancy of Leary’s “Shoot to Live” mantra. For Allen, who was getting heavily into Tibetan Buddhism, meditation was a necessary revolutionary discipline; political action without spiritual consciousness led to the same dead end. Allen put out these ideas in an interview in the Berkeley Barb. Tim responded with “An Open Letter to Allen Ginsberg on the Seventh Liberation,” defending the idea of armed self-defense and explained his new philosophy in poetry.

Brother Allen

It was about time for a loving Call to Arms

Celebrated in mantra SHOOT TO LIVE

Which could have been AIM FOR LIFE

But for energy needed to balance

the SHOOT TO KILL of Police Robots

And certain understandably angry

Brave Young Revolutionaries….

LR: Seems like everybody was publishing open letters to the new Leary.

MH: Actually the first was Charlie Manson from LA County Jail awaiting sentencing. He wrote an open letter to the LA Free Press just weeks after Tim busted out of prison. Manson anointed Tim as his successor, writing “I’ve had my turn, now it’s yours.”

LR: Talk about bad timing!

MH: Totally! Just what Tim needed! An endorsement from the man behind the violent crime spree that freaked out the entire country, and also escalated the demonization of LSD and the hippies by the status quo.

Envelope from Squeaky Fromme to Timothy Leary in Switzerland, containing Manson’s Open Letter to Leary, published a year earlier in the LA Free Press.

Kesey’s open letter appeared in the Rolling Stone in November, congratulating Tim on his escape but taking issue with his call for armed self-defense. (“We don’t need another nut with a gun.”)

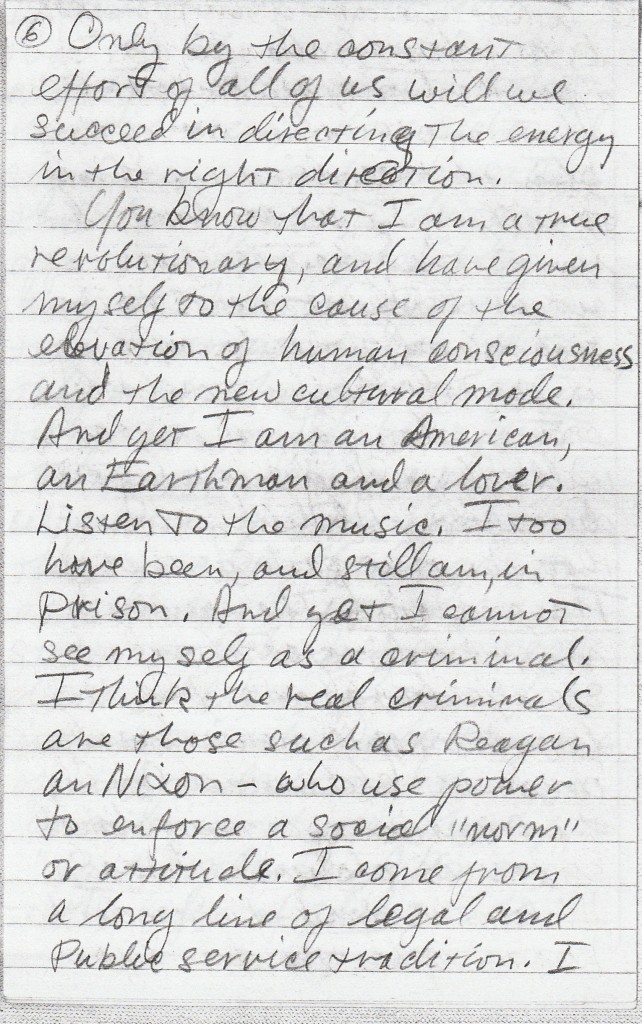

Acid chemist Owsley, whose righteous LSD was the rocket fuel of the early psychedelic movement, wrote him privately from his own jail cell, calling bullshit on Tim’s guerilla trip. He advised him to take a strong dose and look in the mirror. He threw Tim’s famous ‘60s slogan back at him: “Shut up.Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out.”

From Owsley’s letter:

Only by the constant effort of all of us will we succeed in directing the energy in the right direction. You know that I am a true revolutionary, and have given myself to the cause of the elevation of human consciousness and the new cultural mode. And yet I am an American, an Earthman, and a lover. Listen to the music. I too have been, and still am, in prison. And yet I cannot see myself as a criminal. I think the real criminals are those such as Reagan and Nixon—who use power to enforce a social “norm” or attitude…”

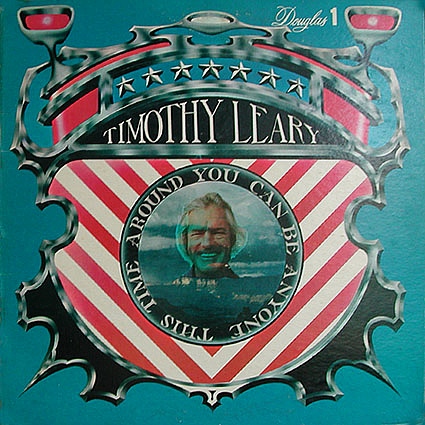

LR: Where did you go after visiting Ginsberg?

MH: We crashed with friends in the East Village and spent several days at Douglas Publishing working with the editor, inserting Leary’s corrections and revisions. Alan Douglas had just released Tim’s latest LP, You Can Be Anyone This Time Around. He lived that title–West Point cadet, psychedelic scientist, founder of an LSD religion, counterculture activist, dissident, prison convict and escapee, candidate for governor of California, peacenik turned militant, cohort of Weatherman and the Black Panthers. He was constantly reinventing himself. It was a hell of a resume and there was a lot more to come.

LR: What about the Ludlow Library? Was it on the back burner?

MH:Not at all. As we passed through every city, we’d hit as many used bookstores as we could, gradually filling up the back of Bob’s VW bug with mind-altering drug literature.

LR: What was Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue like back then?

MH: It was a lot like Haight Street, in San Francisco. It was the face of the urban hippie scene. When we returned in early November, the first letter from the exiles was sitting in the Bodhisattva mailbox at the Sather Gate Post Office in Berkeley. Every radical group, from the Psychedelic Venus Church, to Armed Love, to the Himalayan Trading Company, the Barb and the Tribe, got their mail there.

The copy machines at Kopy Kat were always buzzing till midnight, in constant use by people running off copies of their revolutionary poems and manifestos and announcements of parties and street protests. We fit right in.

We had the archivists’ phobia about losing stuff, so we’d copy everything–manuscripts, letters, news clippings–just so we’d have backups. We were living and caretaking in a crucial historical timezone and every scrap seemed vital. There was always something to do for the Learys and their lawyers, often urgently.

We’d scout books at Moe’s and Shakespeare, then go to the Cafe Med for cappuccino and to look over our finds. In North Beach, we sometimes closed out bookstores that were open till midnight. We were turning into bibliomaniacs and activist-archivists. The Ludlow Library project grounded us from the constant drama, the endless paperwork, and recurring paranoia while functioning as Timothy Leary’s archivists, while he was an international fugitive on the run.

LR: Let’s get back to Algeria. What brought about the “revolutionary bust”?

MH: It was a clash of two strong egos that came to a head two months after the Learys’ arrival in Algiers. Cleaver feared that their care-free hedonism and their stream of counterculture celebrity visitors was putting the Panthers at risk with the Algerian government, and bringing heat. Algiers was crawling with CIA agents and their informants, and the FBI was using its counter-intelligence program to create dissension in the Black Panther party, eventually causing a fatal rift between Newton and Cleaver.

LR: Did Eldridge actually imprison Tim and Rosemary?

MH: The “revolutionary bust” of the Learys was part high school detention for bad behavior and part real imprisonment. They were confined in a series of rooms for five days in early January 1971. They were fearful, not knowing how far it would go, but Cleaver’s intention was only to demonstrate to the international media that he was in charge, and the serious business of revolution was not going to be undermined by a couple of acidheads. A journalist showed up and mediated a session between them. A lengthy transcript was widely published and the media hyped it into a major schism between political and psychedelic revolutionaries.

There was even video footage that made its way onto American television. One night, waiting at the TransBay Terminal for the last bus to Berkeley, I was blown away to see Tim and Eldridge arguing on the giant public television screen. It was very McLuhanesque. KPFA was selling the audio as a fundraiser. It was like a preview of the internet.

LR: Kathleen Cleaver was there too, wasn’t she?

MH: Yes, and their two infant children. Rosemary and Kathleen were like the queenly counterparts of Tim and Eldridge. Rosemary wrote us to have someone do the astrological charts of the Cleaver kids. She was hoping to get pregnant and requesting a chart for her and Tim’s child, but sadly that wasn’t to be.

LR: Were drugs the main cause of their disagreements?

MH: Eldridge considered LSD a dangerous counter–revolutionary distraction. Occasional marijuana use was allowed, but not psychedelics. He made that distinction. He even brought up the standard media charge that Leary had “fried his brain” from too many trips.

The Learys couldn’t cut it as Maoist-style revolutionaries. Their own idea of revolution was neurological rather than political, and had to do with altered states, inner change and creating new paradigms. He and Rosemary spoke of themselves as “change agents” long before it became a pop term.

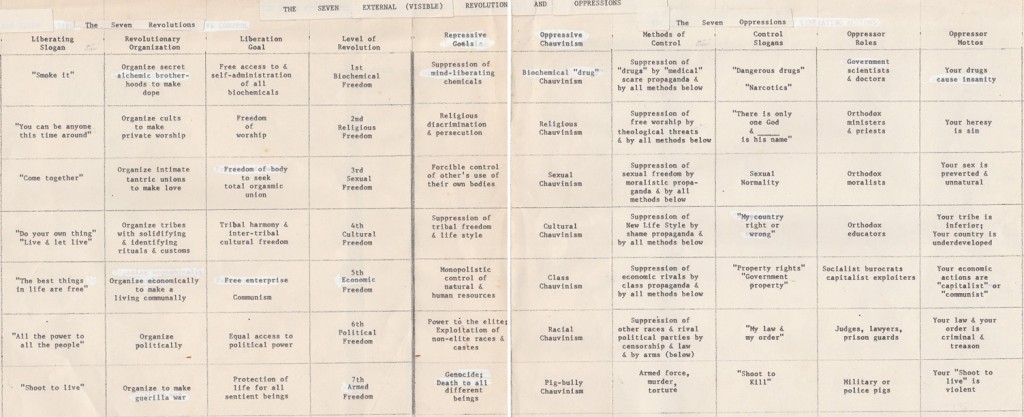

Tim sent us charts he created to describe his latest thinking on the political-cultural zeitgeist. Since his early days as a clinical psychologist, he used charts and grids to synthesize information. He saw these as an occult system, like the Tarot deck and I Ching, channeling new insights and associations.

“The Seven Revolutions and Oppressions”—Leary breakdown of the psychology and politics of control and resistance. (Click to enlarge.)

LR: How closely were you and Bob able to stay in touch with Tim and Rosemary?

MH: We exchanged letters at least once a week. They were constantly needing to know the status of Tim’s articles and book proposals–their primary means of getting money. There were frustrated by issues with their attorneys and book publishers. We sent them news clippings and articles to keep them abreast of how their situation was being portrayed in the media, and to provide documentation for the book Tim was writing–It’s About Time, which was eventually published as Confessions of a Hope Fiend.

Money was a huge problem. We made requests for royalties and for financial help from friends. Allen Ginsberg helped, but a lot of people felt that Tim had burned too many bridges and were unwilling.

LR: Too bad they didn’t have crowdfunding back then.

MH: It would have helped. Their best hope was for an advance for the prison escape book, and that went slowly because of all the challenges of exile. They were also limited by how to write it without putting people at risk. Publishers were not exactly lining up at that point.

Right around this time a young surfer from Laguna Beach stopped by the library to deliver a gift for Tim and Rosemary. He took some handmade Christmas cards from his shoulder bag for us to mail to the Learys. They came from the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, who had set up a global LSD and hashish network, moving million of hits of their potent orange sunshine brand from California to as far as Afghanistan, and bringing back huge quantities of hashish stashed in campers.

LR: Did the Brotherhood of Eternal Love pay the Weatherman Underground to engineer Tim’s escape?

MH: We heard that, but it was pretty hushed up. Seems fitting that LSD helped spring Tim from prison. He and Rosemary had lived in a teepee on Brotherhood land in the mountains above Laguna Beach. It was there where he announced he was running for governor against Reagan, and it was there he was busted for the two marijuana roaches that put him in a California State prison for one to ten years.

LR: So, you mailed the BEL Christmas cards to the Learys in Algiers?

MH: Yeah, with Fitz Hugh Ludlow’s name in the return address.

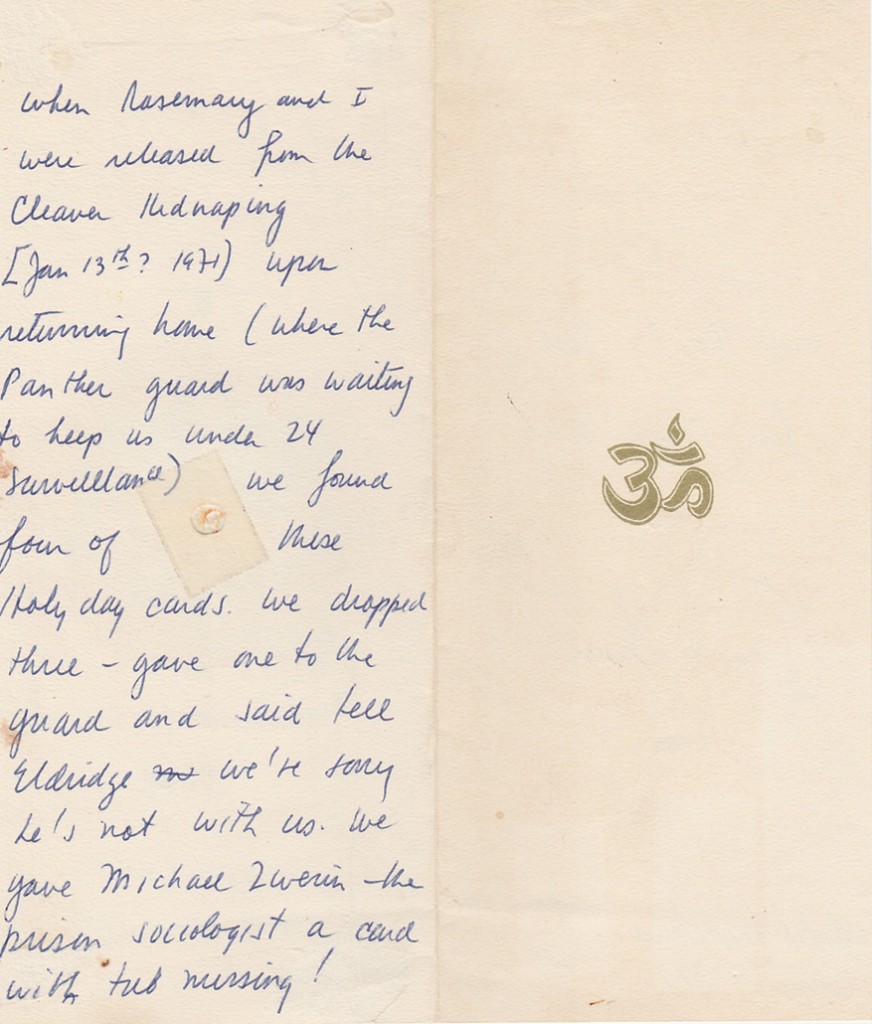

LR: What was the deal exactly with the Christmas Cards?

MH: The inscription tells the story. The traces of orange are where a 300-mic tab of Nick Sand and Tim Scully’s Orange Sunshine LSD was attached to the center of the mandala.

Christmas present from the “Sunshine Family” (Brotherhood of Eternal Love) with Leary’s annotations regarding their use of the gift: “We dropped three–gave one to the guard and said tell Eldridge we’re sorry he’s not with us.” February 1971.

The Learys after release from their “revolutionary bust.” Berkeley Tribe, February 1971. Photo: Alan Copeland

Tim’s note announcing he and Rosemary had been granted asylum by the Algerian government. Horowitz archives

Dear Brothers—All perfect . . . you can tell Max S [Max Scherr, publisher of the Berkeley Barb] that we have been given political asylum by the Algerian government with the freedom to live, conduct our affairs with complete independence under the Algerian law to continue to work for the Revolution—the Freedom Revolution. We send love….”

MH: After they were released from Cleaver’s control, the Learys petitioned the Algerian government for political asylum. Despite the optimism of this letter, they knew that Algeria was no safe haven, and started looking for a way to leave the country.

They were also dead broke. Tim was literally writing and selling manuscripts for dinners during this time. He was in the crosshairs of U.S. agents abroad, and there was the specter of Interpol to consider, especially if they were to go to Europe.

LR: So what did they decide to do?

MH: Their exit from Algeria was real “cloak and dagger.” Tim managed an invitation to speak at a psychology conference in Copenhagen, but had no intention of actually going there. It took them three tries to get a flight out of Algeria, with tickets to Denmark, where they had sent their luggage.

But they changed planes in Paris, and caught a flight to Geneva, where their contact, a wealthy arms dealer (and swindler) with his eyes on the fortune Leary’s next book might make him, was waiting for them at the airport. He put up the Learys in splendor at a chalet in the Alps, wined and dined them extravagantly, and introduced them to one of the top lawyers in Switzerland. This was all hush hush. For weeks, it seemed as if Tim and Rosemary had just disappeared, and there were rumors that he had been kidnapped by the CIA.

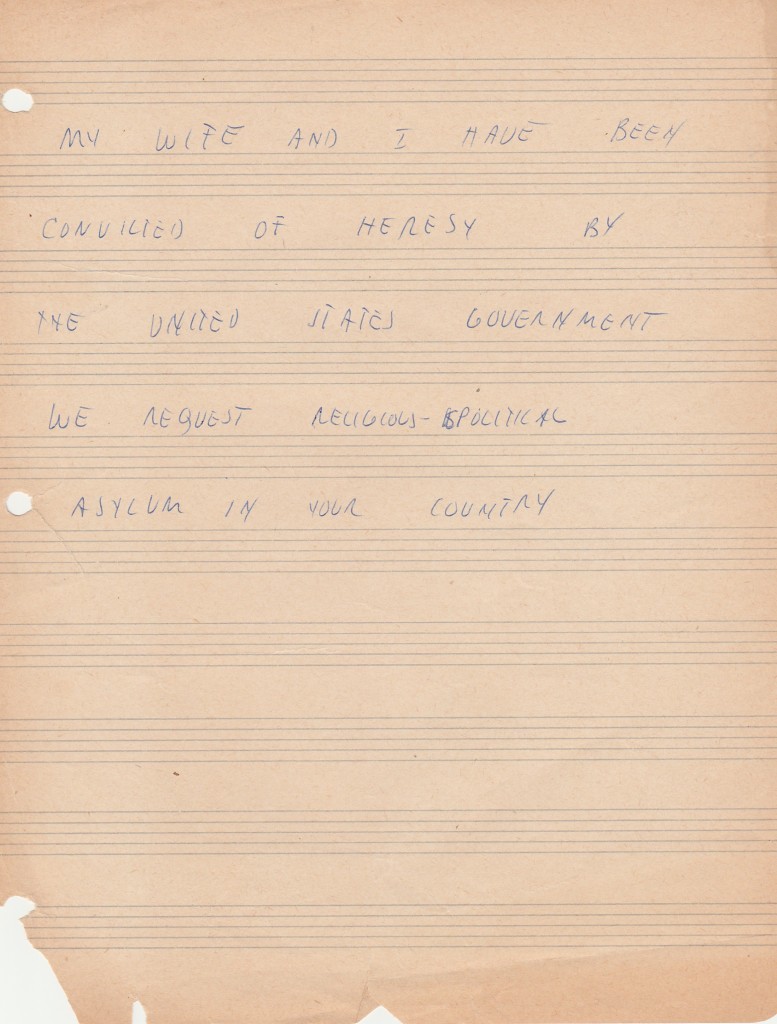

Leary’s handwritten appeal for asylum. Undated, this was probably written during the flight from Algeria, anticipating being detained by authorities either in Denmark, France or Switzerland. Leary Archives, NYPL.

MH: After a couple of weeks of silence a letter came, dated June 24, 1971.

Dear Friends,

So glad to be back in contact with you. We missed you and your continual flow of spirit. For months yours was the only voice of sanity, and I do tell you it got INSANE!!!!! … [Algeria] got comic in the end… so many secret agents and revolutionary masterminds. At one point an allegedly high official arranging for our exit visas in hidden rendezvous spots, literally dark alleys and hidden Arab cafes…we finally caught on that everyone was playing out a James Bond scene. Everyone!!! The exit from A.was so far out. Magical, mysterious, scary, funny.

The second we hit Switzerland a magical network of really divine actors took over. Again so incredible that only you would dig it.

We finally found the tribe we were looking for…

LR: Didn’t Dan Ellsberg leak the Pentagon Papers around that time?

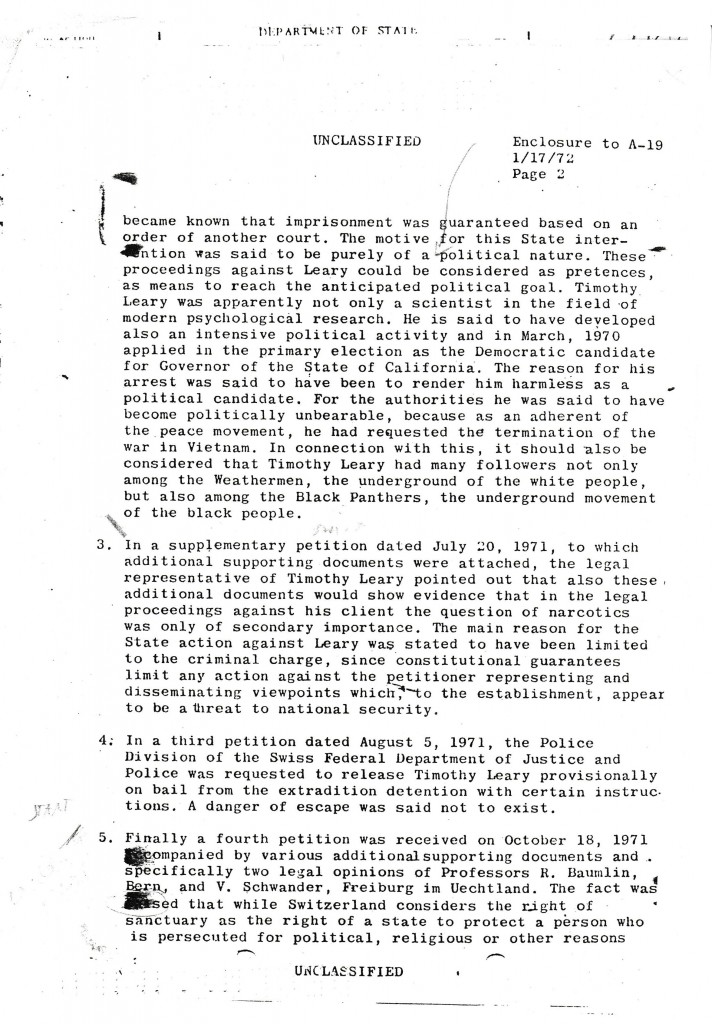

MH: Yes. It was that very month the first leak was published. It was also the month Nixon formally declared his fraudulent War on Drugs. One of his first acts was to demand Tim’s extradition from Switzerland. The Swiss government immediately jailed Leary in Lausanne, while it took up the question. It was his third imprisonment, on three different continents, in less than a year.

Nixon was so intent on apprehending Leary that he sent U.S. Attorney General Mitchell to personally pressure the Swiss authorities to extradite him. This set in motion a wild month for us. Rosemary was once again having to frantically work on the outside for Tim, just as she had when he was in prison in California, but this time, she herself was facing extradition for violating parole.

One day, a desperate letter from her arrived.

Lausanne, July 8, 1971

Tim is in prison in a cold dark cell. Our lawyer in Berne is fighting extradition. The Swiss government requires us to deposit with them many thousands while they consider our case. Please help or Tim and I will never see one another again. We will be in Amerikan prisons for the rest of our lives. I need $120,000 to get Tim out. Extradition order for me but lawyer managed to halt it. Can’t you sell some of the archives and books? This is the last gasp for us. Isn’t there help anywhere?

LR: The U.S. government wanted to extradite Rosemary too?

MH: Yes. For violation of her parole by leaving the country. Unbelievably, she remained on the FBI wanted list for the next 23 years, long after Tim had resolved his legal issues. She was one of the very last political prisoners from that era to surface.

Unfortunately, selling archives was not even an option, as there was no market for it yet, as there is today. No one was collecting him but us.

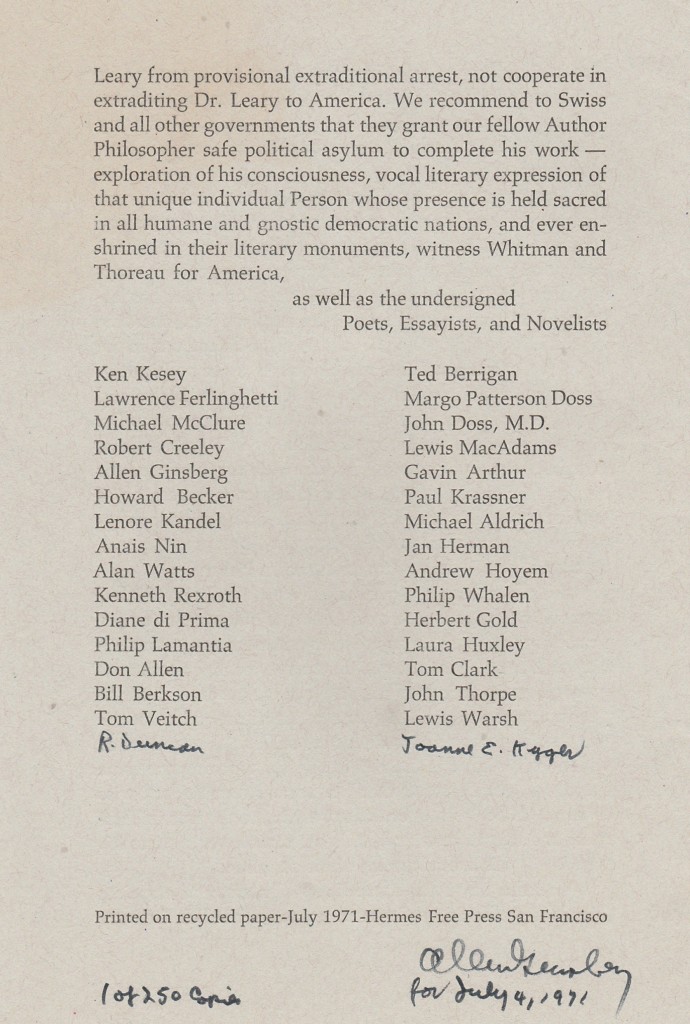

LR: What’s the story behind Ginsberg’s “Declaration of Independence for Timothy Leary?”

MH: We wrote Allen Ginsberg with the latest news of yet another imprisonment of Tim, and he showed up in our little office in North Beach the next day with his arm in a cast. He’d broken it in a fall at Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s cabin in Bixby Canyon the previous week. We’d filled him in on Tim’s situation.

Meanwhile, Allen shared with us that he had patched up a quarrel we were having with Tim, who thought we’d messed up failing to send documents to his Swiss attorney handling the extradition case.

Allen wrote to Tim defending us:

“Barker/Horowitz whatever minor snafus they’ve encountered are invaluable archivists and workers with an office & facilities whence they’ve churned out all the PEN materials & vast files & documents galore faxed in every direction but have no idea if anything has been received… They’re getting (justifiably) depressed.”

MH: Allen was hell-bent on freeing Tim. He made it his mission to rescue Tim as a First Amendment victim—now a “Man Without a Country”–jailed for his writings and ideas. Ginsberg’s plan was to marshal the Western literary world to win the Learys asylum in Switzerland, which had a long record of giving refuge to renegade philosophers, political dissidents and controversial authors.

Ginsberg, Barker and I were the latest in a long line of Leary defense committees. Allen named us the Bay Area Prose Poets Phalanx, with the expectation that other Beat poets would sign on. Eventually, over 30 writers signed on, including: Ken Kesey, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Alan Watts, Anias Nin, Diane di Prima, Laura Huxley and Paul Krassner.

Allen paced the small room as he composed in his head and dictated a 2000-word “Declaration of Independence for Dr. Timothy Leary.” I was the scribe, while Bob acted as the editor on-the-spot, clarifying the flow of language between Allen’s brain and my writing hand.

Allen Ginsberg’s “Declaration of Independence for Dr. Timothy Leary,” dictated to Horowitz and Barker at the Ludlow Library. Title page and last page. Horowitz Archives.

MH: Allen’s words tumbled out in complex sentences. While I typed up this manifesto, Bob combed through his legendary address book—a Who’s Who of the Beat and Hippie literary/activist vanguard.

Once we’d gathered the signatures, we put out a press release. It made the local news. Ginsberg printed up 250 copies which we mailed to the signers. He also personally sent one to the American PEN Center.

Arthur Miller got behind it and PEN wired their support to Leary’s lawyer in Berne. PEN had prestige for supporting oppressed writers anywhere in the world.

Allen forcefully presented Timothy as a maverick scientist and philosopher persecuted for his writings and research who met all the qualifications for asylum. It carried a lot of weight with the Swiss legal authorities. To reject Tim‘s appeal would mean undermining their history of toleration, but unfortunately, they were under tremendous pressure from the US government.

LR: But the Swiss government DID rule in their favor?

MH: Yes. The final determination was that Leary’s crime—possession of two half-smoked marijuana joints—did not require jail time in Switzerland. Other factors played into their decision.

The declassified U.S. State Dept. report on the decision of the Swiss government to not extradite Leary. Leary Archives (NYPL).

From the declassified U.S. State Department Report:

The reason for his arrest was said to have been to render him harmless as a political candidate. For the authorities he was said to have become politically unbearable, because as an adherent of the peace movement, he requested the termination of the war in Vietnam…The question of narcotics was only of secondary importance.”

The Swiss stayed true to their beliefs and freed Leary, granting him temporary asylum. His old friend, the psychedelic theologian Walter Houston Clark, mortgaged his home to help pay the considerable legal costs.

When we next saw Ginsberg to celebrate the Bay Area Prose Poets Phalanx victory in Switzerland, he was already working on a new project; freeing the Living Theater troupe who had been jailed for obscenity in Brazil.

In Tao We Trust. Leary reflecting on his exile experience on a sheet from the League of Spiritual Discovery edition of Psychedelic Prayers, designed by Daniel Raphael. Leary signed it with his false U.S. passport name.

Tim and Rosemary were free and we began to plan our visit to Switzerland.

Coming next — Part 3: Kicked out of Switzerland – Captured in Afghanistan – Back in the California Prison System